Sexual harassment in India: A crisis

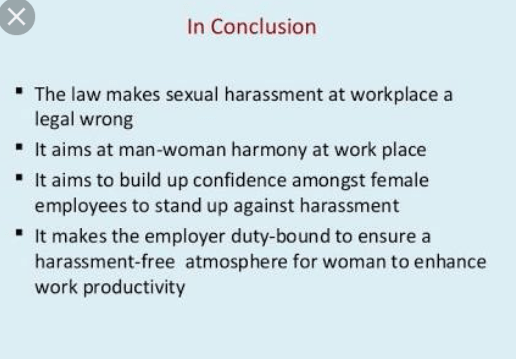

Sexual harassment is frequently overlooked in India, even in the age of the MeToo movement which saw survivors share their stories and led to the downfall of numerous public figures worldwide, in politics, business, the entertainment industry, and beyond.

According to statistics recently released by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), The NCRB data highlighted the plight of women in shelter homes. The maximum number of cases of sexual harassment in shelter homes was reported in Pune, followed by Mumbai. Uttar Pradesh reported more sexual harassment cases in shelter homes than any other state (239), followed by Andhra Pradesh (65) and Maharashtra (64).

Public transport is one of the many places where women can experience sexual harassment in India.

In some respects, this came as good news. “Women are more prompt these days to report any case of sexual misconduct and it is the responsibility of organisations to take speedy action,” said Suresh Tripathi, vice president of human resources management at Tata Steel. “Prompt action by organisations will act as a deterrent for others, and it will encourage women to come out and report.” As such, Tripathi adds, “increased reporting is good to start with as it means there is more awareness.”

Courageous survivors of sexual harassment and assault have had their voices heard and stories believed, thanks to the #MeToo movement. Now, there is renewed energy to make real and lasting change. Our analysis suggests that change is not only possible, but that it is already taking place in a handful of sectors and workplaces. In our accompanying toolkit, we highlight the promising research and practice-informed solutions that are working now and will propel us forward so that all people are able to have agency, respect, and opportunity at work, and to live healthy, secure, and empowered lives.